January 17 marks the 76th anniversary of Raoul Wallenberg’s disappearance in the Soviet Union. Wallenberg experts Susanne Berger and Vadim Birstein present important new information and questions about the circumstances about Wallenberg’s first encounters with Soviet military counterintelligence in Hungary in 1945. Raoul Wallenberg apparently hoped that the Soviet Marshal Rodion Malinovsky would help him to contact Soviet officials in Moscow „or to go there.“ The reason for Wallenberg’s request is not known. If confirmed, such a request may have heightened the distrust of Soviet military and counterintelligence officers of the young Swedish diplomat. It also possibly affected the Swedish government’s response to Wallenberg’s disappearance.

By Susanne Berger and Vadim Birstein

In January 1945, Raoul Wallenberg apparently hoped that the Soviet Marshal Rodion Malinovsky would help him to contact Soviet officials in Moscow „or to go there.“ The reason for Wallenberg’s request is not known. If confirmed, such a request may have heightened the distrust of Soviet military and counterintelligence officers of the young Swedish diplomat. It also possibly affected the Swedish government’s response to Wallenberg’s disappearance.

Quelle: Wikipedia

On a cold morning of January 13, 1945, in Budapest, Raoul Wallenberg met up with a Soviet military intelligence unit of the victorious Red Army that had battled German and Hungarian Nazi forces for months to liberate the city. In the previous nine months, more than 700,000 Hungarian Jews had been deported to death camps in Poland and Germany, in one of the swiftest and most brutal campaigns of the Holocaust. Only approximately 100,000 Jews living in the capital who were protected by neutral countries like Switzerland, Sweden, and the Vatican, managed to survive. Wallenberg, the leader of the Swedish humanitarian action, now wanted to ensure that the Jewish population under his authority would be protected and adequately supplied. Wallenberg had good reasons to be concerned. Widespread reports of Soviet soldiers pillaging, raping women and seizing property had preceded the arrival of the Red Army in Budapest already months earlier.

In 1991, Colonel Ivan Golub, the commander of the Red Army’s 581st Rifle Regiment, recalled his meeting with the young Swedish diplomat:

My first conversation with Wallenberg was about how to help him and his driver to contact Commander of the 2nd Ukrainian Front General [in fact, Marshal] Malinovsky. Through him, he [Wallenberg] wanted to contact Moscow or to get to Moscow [emphasis added]. I was in contact with [Maj. General Ivan] Afonin, Commander of the 18th Rifle Corps, who ordered sending [Wallenberg] to the Headquarters of the 151st Rifle Division.

(Neither the Swedish Working Group Report published in 2000, nor the Eliasson Commission Report released in 2003 mention Golub’s statement that Wallenberg wanted to contact or go to Moscow).

At the time, Marshal Malinovsky clearly had the authority to order military protection for Budapest’s civilian population, including the buildings officially owned by Sweden and other neutral countries that sheltered tens of thousands of Jews. However, if Golub’s account is correct (his recollections were generally very precise), why did Wallenberg express such an urgent wish not only to speak to Marshal Malinovsky, but to contact Soviet officials in Moscow or even to travel there? And did this request draw additional attention from the Soviet political and military counterintelligence officers to Raoul Wallenberg?

Earlier, on December 31, 1944, the Swedish government had transmitted an official request to the Soviet Ministry of Foreign Affairs to protect the group of Swedish diplomats remaining in Budapest. On January 2, 1945, the Soviet General Staff in Moscow sent an order to the 2nd and 3rd Ukrainian fronts, whose troops surrounded Budapest, if members of the Swedish Mission in Budapest were found, “measures to protect this Mission should be taken and immediately reported to the General Staff.” On the list of foreign diplomats that commanders of the fighting units received Wallenberg was identified as Secretary of the Swedish Legation.

Clearly, Colonel Golub’s decision to send the young Swede to Maj. General Afonin, who commanded the Soviet troops fighting in Pest, was made at least partly in response to this official Soviet military order. As Golub explained in 1991, “I decided to do so because, while answering my questions in German, he [Wallenberg] showed me a document, in which I could hardly understand [in German] the word ‘Swedish.’”

Maj. General Ivan. M. Afonin (1904-1979) Source: Герой Советского Союза Афонин Иван Михайлович: Герои страны (warheroes.ru)

Golub’s deputy, Major Leonid Makhrovsky, recalled that from the start, there were some doubts about Wallenberg’s person: “Golub instructed me to take care of the ‘suspicious‘ [quotation marks in the Russian original] diplomat Wallenberg. I immediately fulfilled Wallenberg’s [request] and ordered servicemen to return to him everything that had been previously taken from him.” In gratitude, as Makhrovsky remembered, Wallenberg gave him a cigarette case full of ‘Symphony‘ [brand] cigarettes.”. Makhrovsky also mentioned that the SMERSH Captain, who came to pick up Wallenberg and bring him to the 151st Rifle Division, said that Wallenberg “would be sent to Moscow.”

Wallenberg’s apparent wish to contact or to go to Moscow certainly deserve closer examination.

Wallenberg had previously shared with several colleagues and friends (including the German businessman Ludolph Christensen who met with him in Budapest) his intention of perhaps returning home to Sweden via the Soviet Union. Still, by early 1945, the chaotic and dangerous military situation made leaving Hungary nearly impossible, as Wallenberg indicated in a letter he sent to his mother on December 8, 1944. On the same day, he addressed a separate letter to Kálmán Lauer, a Hungarian Jewish émigré and since 1941 Wallenberg’s business partner in the Swedish import-export company Mellaneuropeiska. Wallenberg wrote that, for the time being, he planned to stay in Budapest. He hoped to create a new organization dedicated to Hungary’s reconstruction and the protection of Jewish property. Upon receipt of this letter, Lauer reported his friend’s plans to the Swedish banker Jacob Wallenberg, Raoul’s relative who had played an important role in his selection for the Budapest mission. Lauer finished his report with a comment that he says was contained in Raoul’s letter: “ He [Raoul Wallenberg] assumes that he at any rate will not be on his way very soon, especially if the journey goes via Russia.“

In fact, no such statement is included in Raoul Wallenberg’s letter of December 8, 1944 to Kálmán Lauer or in the letter Wallenberg addressed to his mother. Why, then, would Lauer relay such a message to Jacob Wallenberg? There is no clear explanation. Possibly, Lauer assumed that Jacob was well apprised of Raoul’s plans from earlier, possibly unknown communications. In late October 1944, Lauer had informed Raoul about the ongoing discussions with the Soviet Trade Delegation in Stockholm. „If you cannot get away in time, “ Lauer wrote, „you will have to travel via Russia, Moscow, and it would be good if you could do some inquiries for us there. I enclose copies of our correspondence with the Russian trade delegation.“ He added: “It is not entirely impossible that I can also come to Moscow, when you are there, but I cannot promise anything, since the formalities make certain difficulties.“

The Swedish historian Georg Sessler has argued that Lauer’s remarks to Wallenberg were, possibly, nothing but an elaborate ruse to hide preparations for the rescue of a group of Hungarian Jews. Nevertheless, it was a well-known fact in Stockholm at the time that leading members of the Wallenberg family, especially Jacob Wallenberg and his brother Marcus (Raoul Wallenberg’s cousins once removed) had a keen interest in pursuing post-war business opportunities with the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe. On July 3, 1944, – a few days before Raoul Wallenberg’s departure for Budapest, – George Labouchère, First Secretary at the British Legation in Stockholm, reported to London:

Marcus Wallenberg has an eye towards business with Russia after the war. … The Swedes lose no opportunity for furthering their business interests and I doubt very much whether this appointment [of Raoul Wallenberg] was entirely disinterested.

Labouchère was definitely correct about Marcus Wallenberg’s eagerness to create close business ties with the Soviets. Already in February 1945, even before the official end of the war, Marcus contacted the Soviet Ambassador Alexandra Kollontay about various large-scale projects, including road construction, as well as the creation of a national telephone service in Poland, which would obviously be in the Soviet sphere of influence after the war. The relationship between the Wallenbergs and Mikhail Nikitin, the Soviet Trade Representative (head of the Soviet Commercial Mission) in Stockholm and a personal confidante of Ambassador Kollontay, was apparently so close that in December 1944, one of the directors of ASEA (a large, Wallenberg controlled Swedish electrical company) reported to Marcus Wallenberg that Nikitin had offered to take up a certain business proposition „as his own “ in Moscow.

Although it is unclear if Soviet diplomats in Stockholm were officially notified of Raoul Wallenberg’s humanitarian mission, they – including Ambassador Kollontay – clearly were informed about it. In a letter to Marcus Wallenberg dated April 22, 1945, Lauer explained: “The Russians should not let anything happen to him [Raoul Wallenberg] since he personally, as well as his mission, enjoyed their strongest sympathies.” Lauer’s statement also implies that Raoul Wallenberg was directly acquainted with at least some Soviet Legation members. That same day Marcus Wallenberg sent a letter to Ambassador Kollontay, asking for her help in determining Raoul Wallenberg’s whereabouts. Kollontay, whose health had declined in the previous year, had returned to the Soviet Union on March 15, 1945 but remained an official employee of the Soviet Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

On the left, Marcus Wallenberg Jr. (1899–1982); on the right, the Soviet Ambassador Alexandra Kollontay (1872–1952)

The correspondence between the Soviet Commercial Mission and Kálmán Lauer and/or Mellaneuropeiska for the years 1941–1944, if it ever existed, has never been released from the Russian archives. It is possible that Wallenberg carried the documents with him on his way to the city of Debrecen, the location of the Hungarian Provisional Government at the time, as well as the headquarters of the SMERSH Directorate of the 2nd Ukrainian Front, or the town of Deszk, the location of the headquarters of Marshal Malinovsky. Some information about this correspondence may still be found in the Wallenberg family business archive or in the archive of Mellaneuropeiska which, so far, has not been recovered.

One has to wonder if the issues that Lauer supposedly wanted Raoul Wallenberg to address with Soviet authorities were pressing enough for Wallenberg to risk a trip of hundreds of miles through an active war zone. It is equally unclear if Mellaneuropeiska’s alleged business plans were in any way connected to Marcus Wallenberg’s undoubtedly much grander post-war ambitions. Most likely, Raoul Wallenberg first and foremost wanted to seek official Soviet support for his extensive plans for the restitution of Jewish property and the economic reconstruction of Hungary which he had begun to develop in November 1944. Together with some of his most trusted Hungarian aides, he intended to create an extensive private aid organization that would be called „The Wallenberg Institute for Rescue and Rehabilitation.“ [Jenö Levai, Pp.118-119, and Pp. 218-228, English edition]. It was clear to Wallenberg that in order to be effective, the planned organization would require official approval and assistance from the Hungarian government and, in particular, from the Soviet occupation authorities. Such plans would have undoubtedly raised Soviet suspicions about Sweden’s, as well as Anglo-American post-war intentions in Hungary.

As the military situation deteriorated, the chances of Raoul Wallenberg traveling home to Sweden via Moscow appeared increasingly unrealistic. Raoul Wallenberg informed one of his aides, Györgyi Szöllösi, during their last meeting that he planned „to go to Debrecen and then continue to Sweden to make his report.“ Again, if Colonel Golub’s account is correct, Raoul Wallenberg may have still felt compelled to establish direct contact with the Soviet authorities in Moscow and possibly to travel there. Wallenberg apparently felt sufficiently protected by the official status afforded to him by his diplomatic passport, even though members of his staff, as well as some of his foreign diplomatic colleagues had repeatedly warned him about the danger of contacting Soviet representatives. Wallenberg must also have certainly been aware that his passport was valid only until December 31, 1944. Per Anger, his colleague at the Swedish Legation, had personally extended it to this date. This means that when Wallenberg met the Soviet military in Budapest on January 13, 1945, he found himself in a certain legal limbo since his most valuable official protective document had, in fact, expired.

Raoul Wallenberg was interrogated in some detail by Soviet officers of the SMERSH (military counterintelligence) Directorate and of the Political Directorate of the 2nd Ukrainian Front. The topics of these interrogations are only partially known. Similarly, virtually no reliable information exists about Wallenberg’s subsequent transfer from Hungary to Moscow. This trip took 11 days (from 25.01.45, 12 pm, to 6.02.45) until he and his driver, the Hungarian citizen Vilmos Langfelder, were formally registered in the Internal (Lubyanka) Prison in Moscow on February 6, 1945.

It is not fully known what Wallenberg’s diplomatic colleagues told Soviet officials when they were themselves detained in February – March 1945.

Unlike Raoul Wallenberg, the members of the Swedish Legation were questioned by officers of the Soviet Internal Affairs Commissariat (NKVD), not SMERSH. In early March, the Swedish Envoy Ivan Danielsson requested a meeting with the Soviet General Ivan Pavlov who commanded the NKVD Troops Guarding the Rear of the 3rd Ukrainian Front. Danielsson asked to discuss certain unspecified activities of the Swedish Legation in Budapest, as well as issues related to Sweden’s representation of Soviet interests in Hungary. Danielsson requested the meeting on March 9, 1945 – one day after Soviet controlled Radio Kossuth had broadcast an announcement that Raoul Wallenberg had been killed, allegedly by „Gestapo agents“. It is not known if Wallenberg’s colleagues were aware of the report.

From left to right: Counselor Lars Berg, First Secretary Per Anger, Minister Carl Ivan Danielsson

Once the group made it to Bucharest (Rumania), Danielsson duly informed the Swedish Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Stockholm that he had notdesignated Raoul Wallenberg as Chargé d’Affaires of the Swedish Legation in Hungary before his departure. In other words, it was unclear if Wallenberg actually held any official position at that moment. Instead, the appointment of Chargé d’Affaires went to the White Russian émigréMikhail Kutuzov-Tolstoy, who had known Danielsson since at least 1943, and had worked closely with Valdemar Langlet who headed the Swedish Red Cross in Budapest. It is known that in 1945, Tolstoy-Kutusov reported to Soviet intelligence officials about the wartime contacts and activities of the Swedish diplomats in Budapest, including those of Raoul Wallenberg. At that time, Kutuzov-Tolstoy worked at the Soviet Military Commandant’s Office and later, in the Soviet Political Department of the Allied Control Commission for Hungary. However, no details of the information about the Swedish diplomats he provided to the Soviets have been released from Russian archives, and his file in the Russian Foreign Intelligence Service (SVR) Archive remains classified.

In short, at a most crucial moment in time, Raoul Wallenberg found himself alone, in prison, without any clear authority and without any official Swedish support. Interestingly, the only Swedish official who seems to have been concerned about Wallenberg’s well being and the lack of clarity about his official status at the time was the Swedish Ambassador to Moscow, Staffan Söderblom. On February 8, 1945, obviously not knowing that Wallenberg had been detained and transferred from Budapest, he asked the Swedish Foreign Ministry in Stockholm „whether Wallenberg in Budapest – who is registered as a Secretary of the Swedish Legation – ought to receive instructions concerning his status.“ When requested to clarify his statement a few days later [on February 13], Söderblom explained [on February 14]:

My thought … was that Wallenberg is instructed to take up contact with the new Hungarian government, which seems [to us] should be regarded as the only legal in the country, in his capacity as official [Swedish] representative. … Some information of this kind seems even more suitable since Wallenberg probably has not gotten the least sign of life from home.

Söderblom may have also felt that it was important to have an official Swedish representative in place in Hungary to drive the search for the other members of the Swedish Legation, Budapest, who were missing at the time. Clearly, Söderblom’s concern about Wallenberg’s status did not last long and his attitude towards Raoul Wallenberg would change sharply once he met with Wallenberg’s colleagues in Moscow on April 13, 1945, on their way to Stockholm. Following that meeting, on April 14, in a cable to Stockholm, he accused Wallenberg of having secretly „sneaked over, on his own initiative, to the Russians“. He also refused to undertake any further steps with the Soviet authorities to clarify Wallenberg’s whereabouts until the Swedish Ministry in Stockholm had had an opportunity to hear the information Wallenberg’s colleagues were able to provide.

Two main questions arise from the foregoing: What could possibly motivate Wallenberg to „sneak over“ to the Soviet forces? And what did the members of the Swedish Legation in Budapest tell Söderblom about Raoul Wallenberg that had made Söderblom so concerned?

It appears quite clear that the accusation of Wallenberg having proceeded on his own accord, without permission, came from one of his own colleagues. During his private meeting with Söderblom in Moscow, the Swedish Minister Ivar Danielsson obviously did not contradict the impression that Wallenberg had acted in an unauthorized manner by directly contacting Soviet officials. Danielsson definitely knew better because, according to the account Per Anger gave to Swedish officials after his return to Stockholm in April 1945, Danielsson had told Wallenberg personally during their last meeting that he was free to establish contact with Soviet representatives, if he felt his situation became untenable.

Yet, apparently rumors persisted within the Swedish Ministry of Foreign Affairs well into the early 1950s that Wallenberg had repeatedly snubbed authority. His colleagues in Budapest described him as „dumb-daring“ and having acted in an „extremely selfish“ manner. The Swedish historian Bengt Jangfeldt has suggested that these claims were possibly linked to Raoul Wallenberg supposedly taking charge of a certain amount of gold and other valuables, without obtaining prior permission, before his departure from Budapest. These items had been stored at the Swedish Legation on behalf of persecuted Jews. There currently exists no clear evidence for this claim.

Others have argued that Wallenberg and his colleagues had provided Swedish protective papers to certain Hungarian and German Nazis, as a bribe to assist him and his aides in protecting the people under their care. Additionally, Swedish war materials, such as ball bearings, had been handed over to Nazi authorities in Hungary as late as October 1944. All these actions, possibly, drew the attention and ire of the Soviet occupation authorities and potentially endangered the lives of Swedish diplomats. Apparently, Söderblom was also concerned that such decidedly „undiplomatic“ behavior would prove to be an irritant for future Swedish-Soviet relations.

Documentation obtained from the archive of the Swedish military intelligence service (MUST) provides a possible additional explanation for Söderblom’s alarm. The documents show that Swedish military intelligence officers were involved in secret operations in Hungary already at the end of 1943, much earlier and to a larger extent than previously known. The operations, conducted in close cooperation with American as well as Hungarian intelligence representatives, aimed not only to support the Hungarian resistance against the Nazi German occupation but also to prevent or at least limit the expected Soviet occupation of Hungary. Swedish – and possibly Raoul Wallenberg’s – direct or indirect association with such activities was especially sensitive because as of June 28, 1941 Sweden officially represented Soviet interests in Hungary.

Therefore, from the official Swedish perspective, the situation at the time of Wallenberg’s disappearance in January 1945 may have looked even more precarious than previously understood. While Wallenberg’s activities in Budapest were mainly humanitarian, his work also involved other aspects, such as efforts to safeguard the extensive economic interests of Sweden and the Western Allies in Hungary. They included, among others, the protection of the professional elite and leading members of the Hungarian society, – businessmen, scientists and technical experts, politicians, diplomats, and lawyers, and in some cases, the protection of their assets. According to the statements of several witnesses, on at least one occasion, Wallenberg transported weapons and ammunition in his diplomatic car for members of the Hungarian resistance and even offered financial support for the purchases of arms and other supplies. This information was first brought to light by the Swedish-Hungarian historian Gellert Kovacs. There are several unconfirmed reports that Raoul Wallenberg and other members of the Swedish Legation collected information about crimes and atrocities committed by the Red Army in Hungary and Poland. Given Wallenberg’s status as a Swedish diplomat, some of his actions would have constituted a violation of Swedish neutrality or at least a serious transgression of diplomatic norms.

Memorandum dated March 3, 1944 on the meeting of Lt. Col. Harry Wester, Swedish Military Attaché in Budapest, Helmuth Ternberg, deputy head of the Swedish C-Bureau and Hungarian Maj. General Ujszászi in February 1944, to discuss a secret Swedish-Hungarian intelligence sharing agreement about Soviet espionage operations in Sweden and Hungary. Source: The Swedish Military intelligence and Security Service Archive (MUST)

The new information obtained from MUST raises the question if the Swedish government’s possible concerns about the public disclosure of its various neutrality violations in Hungary (and elsewhere) may have affected how Swedish officials handled Wallenberg’s disappearance in January 1945. Already in September 1945, Swedish diplomats received information that Wallenberg apparently had been arrested and taken to Moscow and that his papers were to be used in future trials of „leading persons in trade and finance who over the past five years were German friendly.“ The mere rumor of such a public airing of compromising information can only have enhanced Swedish concerns.

So, why did Raoul Wallenberg ask to contact Moscow or to go there? His full motivations for the request remain unknown. Swedish officials may have considered Wallenberg’s actions irresponsible and, possibly, his own colleagues worried about what information he may divulge in the process that could have serious consequences for themselves and, potentially, for the Swedish government as a whole if it became public. It also needs to be determined if Wallenberg’s request in any way influenced the perception and actions of Soviet officials. The answers are almost certainly contained in still unreleased documents of both Swedish and Russian archives.

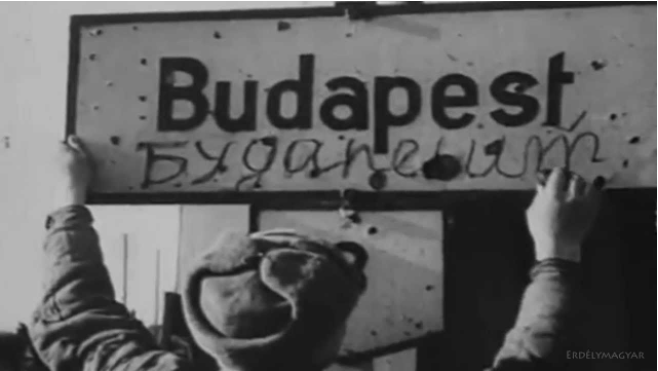

Photo: Header (Soldier writing „Budapest“ in Russian after the Battle of Budapest, Source: Wikipedia.)

Quote: Susanne Berger and Vadim Birstein, „Why did Raoul Wallenberg ask to go to Moscow in January 1945“, in: News, RWI-70, January 17, 2021, URL: http://relaunch.rwi-70.de/why-did-raoul-wallenberg-ask-to-go-to-moscow-in-january-1945/